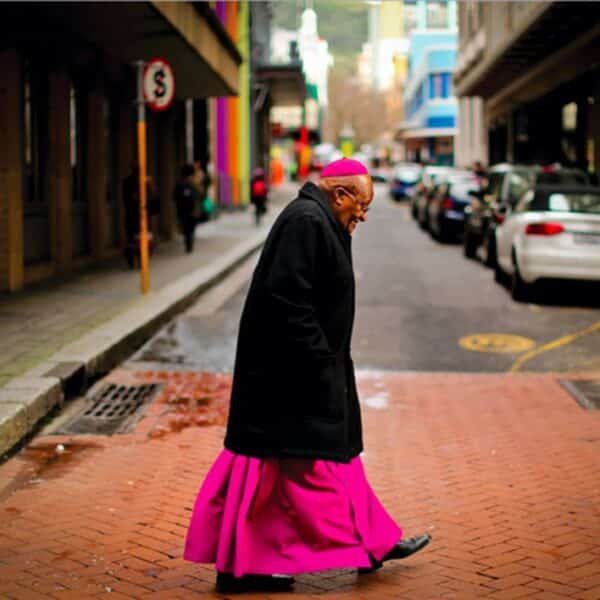

After 16 hours in the air the landing gear dropped for our final descent into a deep red sunset over urban Johannesburg, South Africa. I could feel my achy sleepiness shift into excitement. My wife, Lori, and I had been gifted with the possibility of taking part in the Tutu Travel Seminar, a one-week intensive course centered in Cape Town, South Africa, to study the life and teachings of Archbishop Desmond Tutu. As long-time students and admirers of Desmond Tutu, we were thrilled to have this opportunity. One more flight—this time, a short flight to Cape Town, rated as one of the top five “must-see” cities of the world—and our adventure, together with about a dozen other pilgrims (including the Rev. Ed and Sherre Henley and Dr. Navita James from our own diocese), would begin.

From time learning and praying and hiking in the stunningly beautiful woods and hills of Volmoed Retreat Center, near the coastal town of Hermanus, to walks and meetings and worship in some of the poorest Townships in South Africa, to festive meals at some of the finest restaurants and wineries in the world, to an experience of Robben Island, the prison island where Nelson Mandela and others languished for years, our guides—The Rev. Dr. Michael Battle and the Rev. Edwin Arrison—immersed us into the complex and often contradictory world of Desmond Tutu’s South Africa. Dr. Battle, a seminary professor at The General Theological Seminary, and the Rev. Arrison, Director of the Desmond and Leah Tutu Legacy Foundation (www.tutu.org.za) in Cape Town, had been formed in their priesthood and scholarship through years of intimate work and prayer and life with Archbishop Tutu. Each of them carries his legacy as Elisha carried the mantle of Elijah.

We met some amazing people: a poor Township drama teacher and musician transformed into a global peace builder through his experience of violence during Apartheid (Themba Lonzi); a retired theologian who wrote and spoke against Apartheid in South Africa (John DeGruchy, the “Sage on the Hill”); the first female priest ordained in South Africa (the Rev. Wilma Jacobsen); a Cathedral Dean who had been brutalized by the police for his prophetic work (the Very Rev. Michael Weeder); a local clergy person working among the poor in Zwelihle Township (the Rev. Richard Gallant); a number of young community leaders among the Township poor who had been spiritually formed by the Youth Group at Volmoed to know themselves as beloved children of God when their culture told them otherwise; a “colored” business man whose Anglican background kept him from turning to hate in spite of persecution, and who instead re-enlived his community (Captain Philippus); young scholars continuing the work of Archbishop Tutu in fascinating ways; and clergy, both old and young, who continue working to co-create the holy vision taught and lived by Desmond Tutu.

During our travels and engagements we not only learned but experienced firsthand, the transformative power of Tutu’s ubuntu theology—a theology that draws both from classical Anglicanism and indigenous African thought, reminding us that we are interdependent with one another. Complementing insights from the social sciences, ubuntu affirms that we make one another human. Between the isolation of individualism and the loss of self in communalism is ubunbu: the rich, joyful experience of knowing that “I am… because you are.” This basic concept informed Tutu’s tireless work against Apartheid (the former teaching of the Dutch Reformed Church in South Africa that God wanted separation, not diverse community).

From the perspective of ubuntu Tutu realized that all peoples were damaged by this separation, that when any are victimized, all are victimized, and that the joy and well-being of any includes, by necessity, the joy and well-being of all. God’s will for us is not Babel, separation, but community and interdependence and diversity: the wind of Pentecost, the diversity of tribes in John’s vision that replaces and defines the monolithic “144,000” battle roll in Revelation.

As the Anglican priest John Donne famously wrote centuries ago, “No man is an island.” Ubuntu gives us a context, a concept, and a constructive vocabulary to understand how we are, together, the Body of Christ. Like Christ himself, Tutu focused on the Reign of God rather than scapegoating… yet he never backed down from naming evil and challenging the powers and principalities that were working against the Beloved Community imaged in the heart of God.

Lori and I returned from South Africa both affirmed and changed. While the sites, stories, tours, and beauty of South Africa were all stunning, sharing time with those whose hearts have been transformed through ubuntu was the richest part of our journey. There are so many ways ubuntu can serve us in our own American context; how will we all live out Tutu’s legacy here? For those of us touched by this experience, the answer will play out over the rest of our lives.